phlogiston

turning alchemy into chemistry

The phlogiston theory

Phlogiston theory postulated the existence of a fire-like element called phlogiston contained within combustible bodies and released during combustion.

Empedocles formulated the classical theory that there were four elements—water, earth, fire, and air—and Aristotle reinforced this idea by characterising them as moist, dry, hot, and cold. Fire was thus thought of as a substance, and burning was seen as a process of decomposition that applied only to compounds. Experience had shown that burning was not always accompanied by a loss of material, and a better theory was needed to account for this.

Phlogiston

iMPORTANCE

The theory of phlogiston led to the discovery of oxygen and is seen as the transition between alchemy and chemistry.

Phlogiston

ETYMOLOGY

The name comes from the Ancient Greek φλογιστόν phlogistón (burning up), from φλόξ phlóx (flame).

Phlogiston

Challenge

Phlogiston theory was challenged by the concomitant weight increase and was abandoned before the end of the 18th century.

Phlogiston accounted for combustion via a process that was the inverse of that of the oxygen theory. Phlogisticated substances contain phlogiston and they dephlogisticate when burned, releasing stored phlogiston which is absorbed by the air. Growing plants then absorb this phlogiston, which is why air does not spontaneously combust and also why plant matter burns as well as it does.

"In general, substances that burned in the air were said to be rich in phlogiston; the fact that combustion soon ceased in an enclosed space was taken as clear-cut evidence that air had the capacity to absorb only a finite amount of phlogiston. When the air had become completely phlogisticated it would no longer serve to support the combustion of any material, nor would a metal heated in it yield a calx; nor could phlogisticated air support life. Breathing was thought to take phlogiston out of the body."

Joseph Black's Scottish student Daniel Rutherford discovered nitrogen in 1772, and the pair used the theory to explain his results. The residue of air left after burning, in fact, a mixture of nitrogen and carbon dioxide, was sometimes referred to as phlogisticated air, having taken up all of the phlogiston. Conversely, when Joseph Priestley discovered oxygen, he believed it to be dephlogisticated air, capable of combining with more phlogiston and thus supporting combustion for longer than ordinary air.

During the eighteenth century, as it became clear that metals gained weight after they were oxidized, phlogiston was increasingly regarded as a principle rather than a material substance. By the end of the eighteenth century, for the few chemists who still used the term phlogiston, the concept was linked to hydrogen.

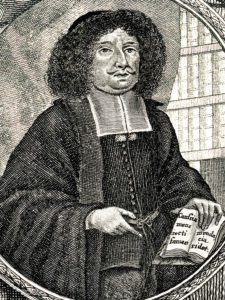

BECHER

His idea that combustible substances contain an ignitable matter, which he called terra pinguis, would become the phlogiston theory

Johann Joachim Becher (1635 – 1682) was a German physician, alchemist, precursor of chemistry, scholar, polymath and adventurer, best known for his development of the phlogiston theory of combustion, and his advancement of Austrian cameralism.

In 1667, Johann Joachim Becher published his book, Physica subterranea, which contained the first instance of what would become the phlogiston theory. In his book, Becher eliminated fire and air from the classical element model and replaced them with three forms of the earth: terra lapidea, terra fluida, and terra pinguis. Terra pinguis was the element that imparted oily, sulphurous, or combustible properties. Becher believed that terra pinguis was a key feature of combustion and was released when combustible substances were burned. Georg Ernst Stahl was Becher's student and further developed the phlogiston theory.

William Cullen considered Becher as a chemist of first importance and Physica Subterranea as the most considerable of Bechers writings.

WORKS

- Works by or about Johann Joachim Becher at Internet Archive

- Johann Joachim Becher-Preises (in German)

- Engines of our Ingenuity: Johann Joachim Becker at uh.edu

- Texts on Wikisource:

- Joh. Joach. Becheri … Opuscula chymica rariora, addita nova praefatione ac indice locupletissimo multisque figuris aeneis illustrata a Friderico Roth-Sholtzio, Siles – full digital facsimile from Linda Hall Library

“Chemistry as an earnest and respectable science is often said to date from 1661, when Robert Boyle of Oxford published The Sceptical Chymist — the first work to distinguish between chemists and alchemists — but it was a slow and often erratic transition. Into the eighteenth century scholars could feel oddly comfortable in both camps — like the German Johann Becher, who produced sober and unexceptionable work on mineralogy called Physica Subterranea, but who also was certain that, given the right materials, he could make himself invisible.”

-Bill Bryson, A Short History of Nearly Everything

STAHL

proposed that metals were made of calx, or ash, and phlogiston and that once a metal is heated, the phlogiston leaves only the calx within the substance

Georg Ernst Stahl (1659–1734) was a German chemist, physician, philosopher and supporter of vitalism.

In 1703, Stahl proposed a variant of the theory in which he renamed Becher's terra pinguis to phlogiston, and it was in this form that the theory probably had its greatest influence.

The term 'phlogiston' itself was not something that Stahl invented. There is evidence that word was used as early as 1606, and in a way that was very similar to what Stahl was using it for. The term was derived from a Greek word meaning inflame.

Stahl's first definition of phlogiston first appeared in his Zymotechnia fundamentalis, published in 1697. His most quoted definition was found in the treatise on chemistry entitled Fundamenta chymiae in 1723. According to Stahl, phlogiston was a substance that was not able to be put into a bottle but could be transferred nonetheless.

To Stahl, wood was just a combination of ash and phlogiston, and making a metal was as simple as getting a metal calx and adding phlogiston. Soot was almost pure phlogiston, which is why heating it with a metallic calx transforms the calx into the metal and Stahl attempted to prove that the phlogiston in soot and sulphur were identical by converting sulphates to liver of sulphur using charcoal. He did not account for the increase in weight on combustion of tin and lead that were known at the time but those who followed his school of thought worked on this problem.

The following paragraph describes Stahl's view of phlogiston:

"To Stahl, metals were compounds containing phlogiston in combination with metallic oxides (calces); when ignited, the phlogiston was freed from the metal leaving the oxide behind. When the oxide was heated with a substance rich in phlogiston, such as charcoal, the calx again took up phlogiston and regenerated the metal. Phlogiston was a definite substance, the same in all its combinations."

Leicester, Henry M.; Klickstein, Herbert S. (1965). A Source Book in Chemistry. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Phlogiston theory did not have any experimental basis before Stahl worked with metals and various other substances in order separate phlogiston from them.

Stahl was able to make phlogiston theory applicable to chemistry as it was one of the first unifying theories in the discipline. Stahl's theory of phlogiston is seen as the transition between alchemy and chemistry. This theory was later replaced by Lavoisier's theory of oxidation and caloric theory.

Until the late 18th century his works on phlogiston were an accepted explanation for chemical processes.

WORKS

- Zymotechnia fundamentalis (1697)

- De lumbricis terrestribus eorumque usu medico (in Latin). Halle: Christian Henckel. 1698.

- Disquisitio de mechanismi et organismi diversitate (1706)

- Paraenesis, ad aliena a medica doctrine arcendum (1706)

- De vera diversitate corporis mixti et vivi (1706)

- Theoria medica vera (1708)

- De lapide manati (in Latin). Halle: Christian Henckel. 1710.

- Georgii Ernesti Stahlii opusculum chymico-physico-medicum : seu schediasmatum, a pluribus annis variis occasionibus in publicum emissorum nunc quadantenus etiam auctorum et deficientibus passim exemplaribus in unum volumen iam collectorum, fasciculus publicae luci redditus / Praemißa praefationis loco authoris epistola ad Michaelem Alberti (1715) Digital edition by the University and State Library Düsseldorf

- Specimen Beccherianum (1718)

- Philosophical Principles of Universal Chemistry (1730), Peter Shaw, translator, from Open Library.

- Experimenta, observationes, animadversiones, 300. numero, chymicae et physicae (in Latin). Berlin: Ambrosius Haude. 1731.

- Materia medica : das ist: Zubereitung, Krafft und Würckung, derer sonderlich durch chymische Kunst erfundenen Artzneyen (1744), Vol. 1&2 Digital edition by the University and State Library Düsseldorf

- Fundamenta chymiae (in Latin). Vol. 3. Nürnberg: Wolfgang Moritz Endter, Erben & Julius Arnold Engelbrecht, Witwe. 1747.

- Fundamenta chymiae (in Latin). Vol. 2. Nürnberg: Wolfgang Moritz Endter, Erben & Julius Arnold Engelbrecht, Witwe. 1746.

- The Leibniz-Stahl Controversy (2016), transl. and edited by F. Duchesneau and J. H. Smith, Yale UP (536 pp.)

Juncker

CONCLUDED phlogiston has the property of levity or that it makes the compound it is in much lighter than it would be without the phlogiston

Johann Juncker (1679 – 1759 ) was a German physician and chemist. Juncker was a leader in the Pietist reform movement as it applied to medicine. He directed the Francke Foundations and initiated approaches to medical practice, charitable treatment, and education at the University of Halle that influenced others internationally. He was a staunch proponent of Georg Ernst Stahl and helped to more clearly present Stahl's phlogiston theory of combustion.

When reading Stahl's work, he assumed that phlogiston was in fact very material. He, therefore, came to the conclusion that phlogiston has the property of levity, or that it makes the compound that it is in much lighter than it would be without the phlogiston. He also showed that air was needed for combustion by putting substances in a sealed flask and trying to burn them.

Juncker published dissertations and books that developed Stahl's vitalist approach. His treatment of Stahl's work on chemical composition and reaction was "critical and coherent", making it easier to understand and reaching a greater audience. He also agreed with Stahl that the disciplines of chemistry and medicine should be treated as distinct. Juncker's Conspectus chemiae theoretico-practicae (1730) systematically explored the work of Stahl and Johann Joachim Becher, and influenced the reception of Stahl's work by eighteenth-century European thinkers including Guillaume-François Rouelle and Immanuel Kant.

As director of an orphanage and its associated medical clinic, Juncker made the practice of volunteering at the clinic (previously an option for medical students) required as part of the medical curriculum. The addition of this Collegium clinicum or practical training to the curriculum led to the expansion of both the medical program and the clinic. Under Juncker's direction, the clinic provided free medical care to thousands of poor patients each year. Juncker's work at Halle inspired the establishment of clinics at Berlin, Göttingen, Jena, and Erfurt.

Juncker wrote and published extensively. In 1721 he published Conspectus chirurgiae, an alphabetical listing describing surgical and obstetrical instruments, bandages, and other medical equipment such as a vaginal cannula for treatment of uterine prolapse. Between 1721 and 1757, 33 editions of Conspectus chirurgiae were published. It is considered one of his most important works, as is Conspectus formularum medicarum.

WORKS

- Conspectus chirurgiae : tam medicae, methodo Stahliana conscriptae, quam instrumentalis, recentissimorum auctorum ductu collectae : quae singula tabulis CIII exhibentur : adjecto indice sufficiente (33 editions 1721-1757)

- Conspectus therapiae generalis : cum notis in materiam medicam tabulis XX methodo Stahliana conscriptus (33 editions 1725-1744)

- Conspectus formularum medicarum : exhibens tabulis XVI tam methodum rationalem, quam remediorum specimina, ex praxi Stahliana potissimum desumta, et therapiae generali accomodata (24 editions 1727-2012)

- Conspectvs chemiae theoretico-practicae : in forma tabvalrvm repraesentatvs, in qvibvs physica, praesertim svbterranea, et corporvm natvralivm principia habitvs inter se, proprietates, vires et vsvs itemqve praecipva chemiae pharmacevticae et mechanicae fvndamenta e dogmatibvs Becheri et Stahlii potissimvm explicantvr, eorvndemqve et aliorvm celebrivm chemicorvm experimentis stabilivntvr (1730)

- Conspectus medicinae theoretico-practicae : tabulis CXXXVIII omnes primarios morbos methodo Stahliana tractandos, exhibens (39 editions 1718-1744)

Library resources about |

| By Johann Juncker |

|---|

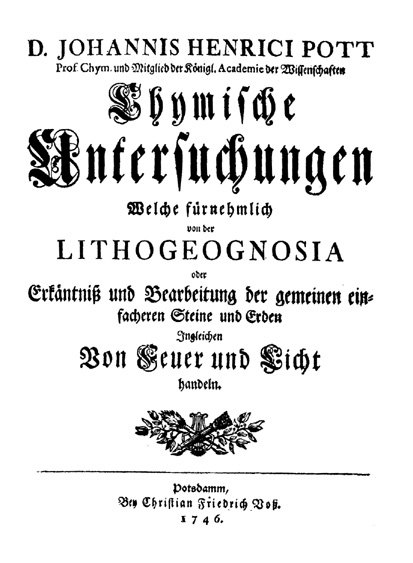

pott

added details and rendered PHLOGISTON theory more approachable to the common man

Johann Heinrich Pott (1692 – 1777) was a Prussian physician and chemist. He is considered a pioneer of pyrochemistry. He examined the elements bismuth and manganese apart from attempting improvements to glass and porcelain production.

Pott, a student of one of Stahl's students, expanded the theory and attempted to make it much more understandable to a general audience. He compared phlogiston to light or fire, saying that all three were substances whose natures were widely understood but not easily defined. He thought that phlogiston should not be considered as a particle but as an essence that permeates substances, arguing that in a pound of any substance, one could not simply pick out the particles of phlogiston. Pott also observed the fact that when certain substances are burned they increase in mass instead of losing the mass of the phlogiston as it escapes; according to him, phlogiston was the basic fire principle and could not be obtained by itself. Flames were considered to be a mix of phlogiston and water, while a phlogiston-and-earthy mixture could not burn properly. Phlogiston permeates everything in the universe, it could be released as heat when combined with an acid.

Pott proposed the following properties:

1. The form of phlogiston consists of a circular movement around its axis.

2. When homogeneous it cannot be consumed or dissipated in a fire.

3. The reason it causes expansion in most bodies is unknown, but not accidental. It is proportional to the compactness of the texture of the bodies or to the intimacy of their constitution.

4. The increase of weight during calcination is evident only after a long time, and is due either to the fact that the particles of the body become more compact, decrease the volume and hence increase the density as in the case of lead, or those little heavy particles of air become lodged in the substance as in the case of powdered zinc oxide.

5. Air attracts the phlogiston of bodies.

6. When set in motion, phlogiston is the chief active principle in nature of all inanimate bodies.

7. It is the basis of colours.

8. It is the principal agent in fermentation.

Pott's formulations proposed little new theory but he supplied further details and rendered existing theory more approachable to the common man.

Pott was the son of the royal councillor Johann Andreas Pott (1662–1729) and Dorothea Sophia daughter of Andreas Machenau. He studied at the cathedral school in Halberstadt and Francke's pedagogium before studying theology at the University of Halle. He then shifted to study medicine and chemistry under Georg Ernst Stahl. In 1713, he studied assaying at Mansfield under mining master Lages. He spent two years with two of his brothers as travelling evangelists for the Community of True Inspiration but he left the sect in 1715 and returned to study chemistry at Halle, receiving a doctorate in 1716 on sulfur under Friedrich Hoffmann. He worked as a physician in Halberstadt before moving to Berlin in 1720 and became a professor of chemistry at the Collegium Medico Chirurgicum in 1724. He succeeded Caspar Neumann (1683–1737) as professor of pharmaceutical chemistry. In 1753 he attempted to get his son-in-law Ernst Gottfried Kurella into a professorship and clashed publicly with Johann Theodor Eller whose student Brandes took the position.

Pott's chemistry contributions included the use of borax and phosphorus beads in analysis. He examined graphite which he differentiated from the contemporary idea that it was lead. Pott established a porcelain factory in Freienwalde under the orders of Frederick II. He examined the composition of pyrolusite.

- Exercitationes chymicae (1738)

- Collectiones observationum et animadversionum chymicarum, 1739 and 1741

- Lithogeognosia (1746–57)

roulle

BROUGHT PHLOGISTON THEORY TO FRANCE

Guillaume François Rouelle (1703 – 1770) was a French chemist and apothecary. In 1754 he introduced the concept of a base into chemistry as a substance which reacts with an acid to form a salt. He is known as l'Aîné (the elder) to distinguish him from his younger brother, Hilaire Rouelle, who was also a chemist and known as the discoverer of urea.

Guillaume-François Rouelle brought the theory of phlogiston to France, and he was a very influential scientist and teacher so it gained quite a strong foothold very quickly. Many of his students became very influential scientists in their own right, Lavoisier included. The French viewed phlogiston as a very subtle principle that vanishes in all analysis, yet it is in all bodies. Essentially they followed straight from Stahl's theory.

Rouelle started as an apothecary. He later started a public course in his laboratory in 1738, in 1742 he was appointed experimental demonstrator of chemistry at the Jardin du Roi in Paris. he was especially influential and popular as a teacher, and taught many students among whom were Denis Diderot, Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier, Joseph Proust and Antoine-Augustin Parmentier.

In addition to his investigation of neutral salts, he published papers on the inflammation of turpentine and other essential oils by nitric acid, and the methods of embalming practised in Ancient Egypt.

FURTHER READING

- Franckowiak, Rémi (2003). “Rouelle, un vrai-faux anti-newtonien”. Archives internationales d’histoire des sciences. 53 (150–151): 240–255.

- Franckowiak, Rémi (2002). “Les sels neutres de Guillaume-François Rouelle” (PDF). Revue d’Histoire des Sciences. 55 (4): 493–532. doi:10.3406/rhs.2002.2163.

- Lemay, Pierre; Oesper, Ralph E. (1954). “The lectures of Guillaume Francois Rouelle”. The Journal of Chemical Education. 31 (7): 338. Bibcode:1954JChEd..31..338L. doi:10.1021/ed031p338.

- Warolin, C. (1996). “Did Lavoisier benefit from the teachings of the apothecary Guillaume-François Rouelle?”. Histoire des sciences médicales. 30 (1): 30. PMID 11624829.

- Warolin, C. (1995). “Did Lavoisier benefit from the teachings of the apothecary Guillaume-François Rouelle?”. Revue d’histoire de la pharmacie. 42 (307): 361–367. doi:10.3406/pharm.1995.4257. PMID 11624913.

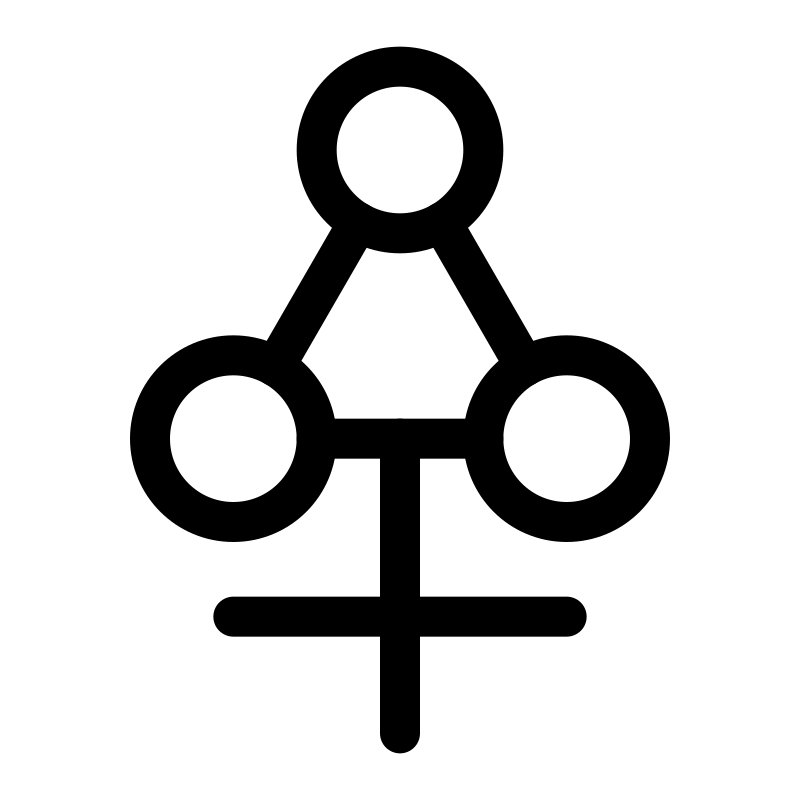

bergman

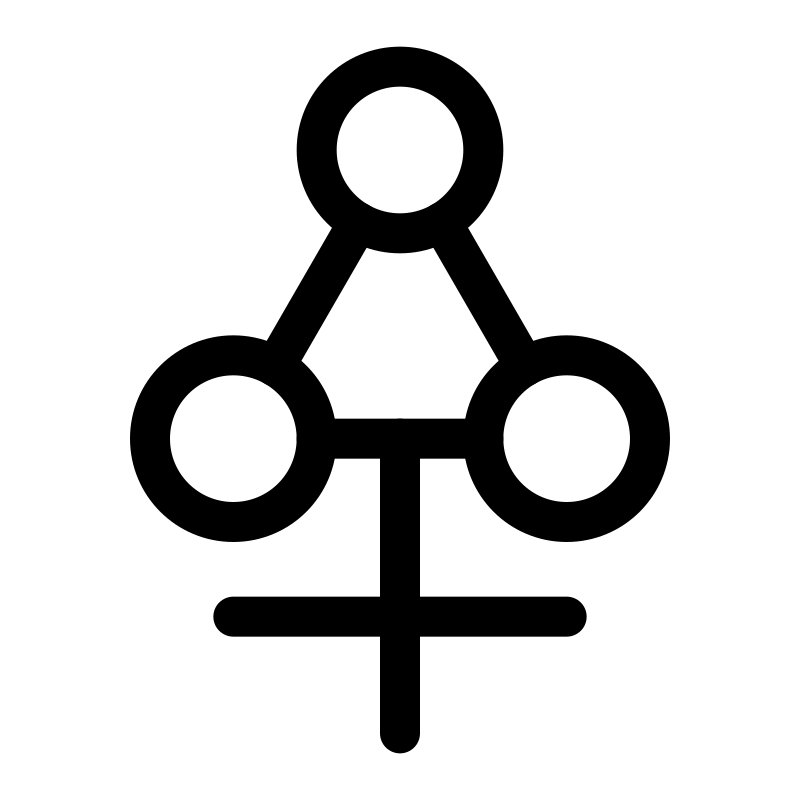

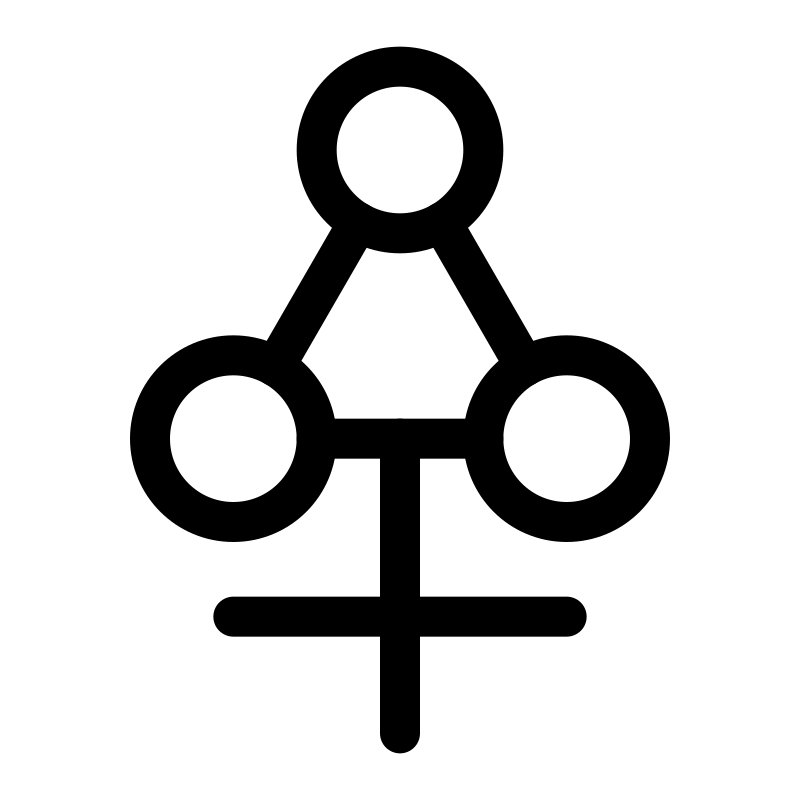

DESIGNED PHLOGISTON SYMBOLS

Torbern Olaf (Olof) Bergman (1735 –1784) was a Swedish chemist and mineralogist noted for his 1775 Dissertation on Elective Attractions, containing the largest chemical affinity tables ever published. Bergman was the first chemist to use the A, B, C, etc., system of notation for chemical species.

In 1756 he succeeded in proving that, contrary to the opinion of Linnaeus, the so-called Coccus aquaticus was really the ovum of a kind of leech.

Bergman greatly contributed to the advancement of quantitative analysis, and he developed a mineral classification scheme based on chemical characteristics and appearance. He is noted for his research on the chemistry of metals, especially bismuth and nickel.

In 1771, six years after he first discovered carbonated water and four years after Joseph Priestley first created artificially carbonated water, Bergman perfected a process to make carbonated water from chalk by the action of sulphuric acid. He is also noted for his sponsorship of Carl Wilhelm Scheele, whom some deem to be Bergman's "greatest discovery". The translation into English of his book Physical and Chemical Essays was read widely and regarded as the first systematic method of chemical analysis.

The uranium mineral torbernite and the lunar crater Bergman both bear his name.

He is said to have designed the symbol for phlogiston.

WORKS

- Physick Beskrifning Ofver Jordklotet. 1766.

- Opuscula physica et chemica (in Latin). Vol. 1. Stockholm: Magnus Swederus. 1779.

- Opuscula physica et chemica (in Latin). Vol. 2. Uppsala: John Edman. 1780.

- Opuscula physica et chemica (in Latin). Vol. 3. Leipzig: Johann Gottfried Müller. 1786.

- Opuscula physica et chemica (in Latin). Vol. 4. Leipzig: Johann Gottfried Müller. 1787.

- Opuscula physica et chemica (in Latin). Vol. 5. Leipzig: Johann Gottfried Müller. 1788.

- Bergman, Torbern (1775). A Dissertation on Elective Attractions.

- Essays, Physical and Chemical. 1779–1781.

- Historiae chemiae medium seu obscurum aevum (in Italian). Firenze: Giuseppe Tofani. 1782.

- Tekniska Museet

priestley

independent disovery of oxygen, which he called dephlogisticated air, by thermal decomposition of mercuric oxide

Joseph Priestley FRS (1733 – 1804) was an English chemist, natural philosopher, separatist theologian, grammarian, multi-subject educator, and liberal political theorist. He published over 150 works, and conducted experiments in several areas of science.

A blue plaque from the Royal Society of Chemistry commemorates Priestley at New Meeting Street, Birmingham.

Priestley is credited with his independent discovery of oxygen by the thermal decomposition of mercuric oxide, having isolated it in 1774.

During his lifetime, Priestley's considerable scientific reputation rested on his invention of carbonated water, his writings on electricity, and his discovery of several "airs" (gases), the most famous being what Priestley dubbed "dephlogisticated air" (oxygen).

Priestley's determination to defend phlogiston theory and to reject what would become the chemical revolution eventually left him isolated within the scientific community.

During the eighteenth century, as it became clear that metals gained weight after they were oxidized, phlogiston was increasingly regarded as a principle rather than a material substance.

By the end of the eighteenth century, for the few chemists who still used the term phlogiston, the concept was linked to hydrogen.

Joseph Priestley, for example, in referring to the reaction of steam on iron, while fully acknowledging that the iron gains weight after it binds with oxygen to form a calx, iron oxide, iron also loses "the basis of inflammable air (hydrogen), and this is the substance or principle, to which we give the name phlogiston".

Following Lavoisier's description of oxygen as the oxidizing principle (hence its name, from Ancient Greek: oksús, "sharp"; génos, "birth" referring to oxygen's supposed role in the formation of acids), Priestley described phlogiston as the alkaline principle.

Priestley's years in Calne were the only ones in his life dominated by scientific investigations; they were also the most scientifically fruitful. His experiments were almost entirely confined to "airs", and out of this work emerged his most important scientific texts: the six volumes of Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air (1774–86). These experiments helped repudiate the last vestiges of the theory of four elements, which Priestley attempted to replace with his own variation of phlogiston theory. According to that 18th-century theory, the combustion or oxidation of a substance corresponded to the release of a material substance, phlogiston.

Priestley's work on "airs" is not easily classified. As historian of science Simon Schaffer writes, it "has been seen as a branch of physics, or chemistry, or natural philosophy, or some highly idiosyncratic version of Priestley's own invention". Furthermore, the volumes were both a scientific and a political enterprise for Priestley, in which he argues that science could destroy "undue and usurped authority" and that government has "reason to tremble even at an air pump or an electrical machine".

Volume I of Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air outlined several discoveries: "nitrous air" (nitric oxide, NO); "vapor of spirit of salt", later called "acid air" or "marine acid air" (anhydrous hydrochloric acid, HCl); "alkaline air" (ammonia, NH3); "diminished" or "dephlogisticated nitrous air" (nitrous oxide, N2O); and, most famously, "dephlogisticated air" (oxygen, O2) as well as experimental findings that showed plants revitalised enclosed volumes of air, a discovery that would eventually lead to the discovery of photosynthesis.

Priestley also developed a "nitrous air test" to determine the "goodness of air". Using a pneumatic trough, he would mix nitrous air with a test sample, over water or mercury, and measure the decrease in volume—the principle of eudiometry. After a small history of the study of airs, he explained his own experiments in an open and sincere style. As an early biographer writes, "whatever he knows or thinks he tells: doubts, perplexities, blunders are set down with the most refreshing candour." Priestley also described his cheap and easy-to-assemble experimental apparatus; his colleagues therefore believed that they could easily reproduce his experiments. Faced with inconsistent experimental results, Priestley employed phlogiston theory. This led him to conclude that there were only three types of "air": "fixed", "alkaline", and "acid". Priestley dismissed the burgeoning chemistry of his day. Instead, he focused on gases and "changes in their sensible properties", as had natural philosophers before him. He isolated carbon monoxide (CO), but apparently did not realise that it was a separate "air".

More details Dumourier Dining in State at St James's, on the 15th of May, 1793 by James Gillray. Published 30 March 1793 by H. Humphrey, No. 18 Old Bond Street. “One of Gillray’s finest efforts, particularly impressive in colored impressions. Priestley bearing a mitre-crowned pie, Fox carrying the steaming head of Pitt on a platter garnished with frogs, and Sheridan holding the royal crown on a salver approach a table at which is seated the tatterdemalion figure of the French General Dumourier. Dumourier’s rumored invasion of England was never to take place but the nature of the trio’s putative allegiance and of their 'treasons in embrio' are marvelously evolved.” (British Museum # 8318).

-

Daventry Academy

-

Needham Market and Nantwich (1755–1761)

Warrington Academy (1761–1767)

- Educator and historianHistory of electricity

-

Minister of Mill Hill Chapel

-

Religious controversialist

-

Defender of Dissenters and political philosopher

-

Natural philosopher: electricity, Optics, and carbonated water

-

Materialist philosopher

-

Founder of British Unitarianism

-

Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air

-

Discovery of oxygen

-

Chemical Revolution

-

Defender of English Dissenters and French revolutionaries

- Religious Activity

- Controversy

- Family Problems

- Death

WORKS

Archives

Papers of Joseph Priestley are held at the Cadbury Research Library, University of Birmingham.

Selected works

Library resources about |

| By Joseph Priestley |

|---|

- The Rudiments of English Grammar (1761)

- A Chart of Biography (1765)

- Essay on a Course of Liberal Education for Civil and Active Life (1765)

- The History and Present State of Electricity (1767)

- Essay on the First Principles of Government (1768)

- A New Chart of History (1769)

- Institutes of Natural and Revealed Religion (1772–74)

- Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air (1774–77)

- Disquisitions Relating to Matter and Spirit (1777)

- The Doctrine of Philosophical Necessity Illustrated (1777)

- Letters to a Philosophical Unbeliever (1780)

- An History of the Corruptions of Christianity (1782)

- Lectures on History and General Policy (1788)

- Theological Repository (1770–73, 1784–88)

See also

- List of independent discoveries

- List of liberal theorists

- Timeline of hydrogen technologies

- Bibliography of Benjamin Franklin — Many works on Franklin make reference to Priestley

"A Word of Comfort" by William Dent (dated 22 March 1790). Priestley is preaching in front of Charles James Fox who asks "Pray, Doctor, is there such a thing as a Devil?", to which Priestley responds "No" while the devil prepares to attack Priestley from behind.

"The Friends of the People", Isaac Cruikshank (1764–1811), Scottish painter and caricaturist, London, 15 November 1792, hand-colored etching, published by S. W. Fores, No. 3 Piccadilly. In his time, Priestley’s scientific contributions were overshadowed by his Unitarian beliefs and somewhat radical views on reforming society. Here Joseph Priestley is seen seated at a table with Thomas Paine, radical supporter of the American and French revolutions, surrounded by incendiary items: guns, knives, a dish says phosphorous, a gun butt says “Royal Electric fluid.” A winged putto grins at them while squatting on the table. Thomas Paine sits upon kegs of gunpowder. Books on treason, murders, assassination, revolution, etc. surround them. At Priestley’s feet are packages of brimstone, axe, and pickax. On the walls are scenes of execution and assassinations.

lavoisier

He named oxygen, recognizED it as an element, and also recognized hydrogen as an element, opposing the phlogiston theory

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier (1743 – 1794), also Antoine Lavoisier after the French Revolution, was a French nobleman and chemist who was central to the 18th-century chemical revolution and who had a large influence on both the history of chemistry and the history of biology.

It is generally accepted that Lavoisier's great accomplishments in chemistry stem largely from his changing the science from a qualitative to a quantitative one.

Lavoisier is most noted for his discovery of the role oxygen plays in combustion. He named oxygen (1778), recognizing it as an element, and also recognized hydrogen as an element (1783), opposing the phlogiston theory.

He predicted the existence of silicon (1787) and discovered that, although matter may change its form or shape, its mass always remains the same.

Contributions to Chemistry

OXYGEN THEORY OF COMBUSTION

Contrary to prevailing thought at the time, Lavoisier theorized that common air, or one of its components, combines with substances when they are burned. He demonstrated this through experiment.

During late 1772 Lavoisier turned his attention to the phenomenon of combustion, the topic on which he was to make his most significant contribution to science. He reported the results of his first experiments on combustion in a note to the Academy on 20 October, in which he reported that when phosphorus burned, it combined with a large quantity of air to produce acid spirit of phosphorus, and that the phosphorus increased in weight on burning. In a second sealed note deposited with the Academy a few weeks later (1 November) Lavoisier extended his observations and conclusions to the burning of sulfur and went on to add that "what is observed in the combustion of sulfur and phosphorus may well take place in the case of all substances that gain in weight by combustion and calcination: and I am persuaded that the increase in weight of metallic calces is due to the same cause."[citation needed]

JOSEPH BLACK'S 'FIXED AIR'

During 1773 Lavoisier determined to review thoroughly the literature on air, particularly "fixed air," and to repeat many of the experiments of other workers in the field. He published an account of this review in 1774 in a book entitled Opuscules physiques et chimiques (Physical and Chemical Essays). In the course of this review, he made his first full study of the work of Joseph Black, the Scottish chemist who had carried out a series of classic quantitative experiments on the mild and caustic alkalies. Black had shown that the difference between a mild alkali, for example, chalk (CaCO3), and the caustic form, for example, quicklime (CaO), lay in the fact that the former contained "fixed air," not common air fixed in the chalk, but a distinct chemical species, now understood to be carbon dioxide (CO2), which was a constituent of the atmosphere. Lavoisier recognized that Black's fixed air was identical with the air evolved when metal calces were reduced with charcoal and even suggested that the air which combined with metals on calcination and increased the weight might be Black's fixed air, that is, CO2.[citation needed]

JOSEPH PRIESTLEY

In the spring of 1774, Lavoisier carried out experiments on the calcination of tin and lead in sealed vessels, the results of which conclusively confirmed that the increase in weight of metals in combustion was due to combination with air. But the question remained about whether it was in combination with common atmospheric air or with only a part of atmospheric air. In October the English chemist Joseph Priestley visited Paris, where he met Lavoisier and told him of the air which he had produced by heating the red calx of mercury with a burning glass and which had supported combustion with extreme vigor. Priestley at this time was unsure of the nature of this gas, but he felt that it was an especially pure form of common air. Lavoisier carried out his own research on this peculiar substance. The result was his memoir On the Nature of the Principle Which Combines with Metals during Their Calcination and Increases Their Weight, read to the Academy on 26 April 1775 (commonly referred to as the Easter Memoir). In the original memoir, Lavoisier showed that the mercury calx was a true metallic calx in that it could be reduced with charcoal, giving off Black's fixed air in the process. When reduced without charcoal, it gave off an air which supported respiration and combustion in an enhanced way. He concluded that this was just a pure form of common air and that it was the air itself "undivided, without alteration, without decomposition" which combined with metals on calcination.[citation needed]

After returning from Paris, Priestley took up once again his investigation of the air from mercury calx. His results now showed that this air was not just an especially pure form of common air but was "five or six times better than common air, for the purpose of respiration, inflammation, and ... every other use of common air". He called the air dephlogisticated air, as he thought it was common air deprived of its phlogiston. Since it was therefore in a state to absorb a much greater quantity of phlogiston given off by burning bodies and respiring animals, the greatly enhanced combustion of substances and the greater ease of breathing in this air were explained.[citation needed]

CHEMICAL NOMENCLATURE

CHEMICAL REVOLUTION AND OPPOSITION

Notable works

DISMANTLING PHLOGISTON THEORY

Lavoisier's chemical research between 1772 and 1778 was largely concerned with developing his own new theory of combustion. In 1783 he read to the academy his paper entitled Réflexions sur le phlogistique (Reflections on Phlogiston), a full-scale attack on the current phlogiston theory of combustion.

That year Lavoisier also began a series of experiments on the composition of water which were to prove an important capstone to his combustion theory and win many converts to it.

Many investigators had been experimenting with the combination of Henry Cavendish's inflammable air, now known as hydrogen, with "dephlogisticated air" (air in the process of combustion, now known to be oxygen) by electrically sparking mixtures of the gases. All of the researchers noted Cavendish's production of pure water by burning hydrogen in oxygen, but they interpreted the reaction in varying ways within the framework of phlogiston theory.

Lavoisier learned of Cavendish's experiment in June 1783 via Charles Blagden (before the results were published in 1784), and immediately recognized water as the oxide of a hydroelectric gas.

In cooperation with Laplace, Lavoisier synthesized water by burning jets of hydrogen and oxygen in a bell jar over mercury. The quantitative results were good enough to support the contention that water was not an element, as had been thought for over 2,000 years, but a compound of two gases, hydrogen and oxygen. The interpretation of water as a compound explained the inflammable air generated from dissolving metals in acids (hydrogen produced when water decomposes) and the reduction of calces by inflammable air (a combination of gas from calx with oxygen to form water).

Despite these experiments, Lavoisier's antiphlogistic approach remained unaccepted by many other chemists. Lavoisier labored to provide definitive proof of the composition of water, attempting to use this in support of his theory.

Working with Jean-Baptiste Meusnier, Lavoisier passed water through a red-hot iron gun barrel, allowing the oxygen to form an oxide with the iron and the hydrogen to emerge from the end of the pipe. He submitted his findings of the composition of water to the Académie des Sciences in April 1784, reporting his figures to eight decimal places.

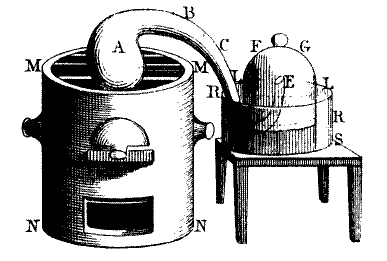

Opposition responded to this further experimentation by stating that Lavoisier continued to draw the incorrect conclusions and that his experiment demonstrated the displacement of phlogiston from iron by the combination of water with the metal. Lavoisier developed a new apparatus which used a pneumatic trough, a set of balances, a thermometer, and a barometer, all calibrated carefully. Thirty savants were invited to witness the decomposition and synthesis of water using this apparatus, convincing many who attended of the correctness of Lavoisier's theories.

This demonstration established water as a compound of oxygen and hydrogen with great certainty for those who viewed it. The dissemination of the experiment, however, proved subpar, as it lacked the details to properly display the amount of precision taken in the measurements. The paper ended with a hasty statement that the experiment was "more than sufficient to lay hold of the certainty of the proposition" of the composition of water and stated that the methods used in the experiment would unite chemistry with the other physical sciences and advance discoveries.

THERE IS A SEPARATE NOTE COVERING THE FOLLOWING TOPICS:

BIOGRAPHY

- Early life and education

- Early scientific work

- Lavoisier as a social reformer

- Research benefitting the public good

- Sponsorship of the sciences

Ferme générale and marriage

- Adulteration of tobacco

- Royal Commission on Agriculture

- Gunpowder Commission

- During the Revolution

- Final days and execution

- Exoneration

- Oxygen theory of combustion

- Joseph Black’s “fixed air”

- Joseph Priestley

- Pioneer of stoichiometry

- Chemical nomenclature

- Chemical revolution and opposition

Notable works

- Easter memoir

- Dismantling phlogiston theory

- Elementary Treatise of Chemistry

- Physiological work

- Awards and honours

WORKS

- Opuscules physiques et chimiques (Paris: Chez Durand, Didot, Esprit, 1774). (Second edition, 1801)

- L’art de fabriquer le salin et la potasse, publié par ordre du Roi, par les régisseurs-généraux des Poudres & Salpêtres (Paris, 1779).

- Instruction sur les moyens de suppléer à la disette des fourrages, et d’augmenter la subsistence des bestiaux, Supplément à l’instruction sur les moyens de pourvoir à la disette des fourrages, publiée par ordre du Roi le 31 mai 1785 (Instruction on the means of compensating for the food shortage with fodder, and of increasing the subsistence of cattle, Supplement to the instruction on the means of providing for the food shortage with fodder, published by order of King on 31 May 1785).

- (with Guyton de Morveau, Claude-Louis Berthollet, Antoine Fourcroy) Méthode de nomenclature chimique (Paris: Chez Cuchet, 1787)

- (with Fourcroy, Morveau, Cadet, Baumé, d’Arcet, and Sage) Nomenclature chimique, ou synonymie ancienne et moderne, pour servir à l’intelligence des auteurs. (Paris: Chez Cuchet, 1789)

- Traité élémentaire de chimie, présenté dans un ordre nouveau et d’après les découvertes modernes (Paris: Chez Cuchet, 1789; Bruxelles: Cultures et Civilisations, 1965) (lit. Elementary Treatise on Chemistry, presented in a new order and alongside modern discoveries) also here

- (with Pierre-Simon Laplace) “Mémoire sur la chaleur,” Mémoires de l’Académie des sciences (1780), pp. 355–408.

- Mémoire contenant les expériences faites sur la chaleur, pendant l’hiver de 1783 à 1784, par P.S. de Laplace & A. K. Lavoisier (1792)

- Mémoires de Physique et de Chimie, de la Société d’Arcueil (1805: posthumous)

In translation

- Essays Physical and Chemical (London: for Joseph Johnson, 1776; London: Frank Cass and Company Ltd., 1970) translation by Thomas Henry of Opuscules physiques et chimiques

- The Art of Manufacturing Alkaline Salts and Potashes, Published by Order of His Most Christian Majesty, and approved by the Royal Academy of Sciences (1784) trans. by Charles Williamos[65] of L’art de fabriquer le salin et la potasse

- (with Pierre-Simon Laplace) Memoir on Heat: Read to the Royal Academy of Sciences, 28 June 1783, by Messrs. Lavoisier & De La Place of the same Academy. (New York: Neale Watson Academic Publications, 1982) trans. by Henry Guerlac of Mémoire sur la chaleur

- Essays, on the Effects Produced by Various Processes On Atmospheric Air; With A Particular View To An Investigation Of The Constitution Of Acids, trans. Thomas Henry (London: Warrington, 1783) collects these essays:

- “Experiments on the Respiration of Animals, and on the Changes effected on the Air in passing through their Lungs.” (Read to the Académie des Sciences, 3 May 1777)

- “On the Combustion of Candles in Atmospheric Air and in Dephlogistated Air.” (Communicated to the Académie des Sciences, 1777)

- “On the Combustion of Kunckel’s Phosphorus.”

- “On the Existence of Air in the Nitrous Acid, and on the Means of decomposing and recomposing that Acid.”

- “On the Solution of Mercury in Vitriolic Acid.”

- “Experiments on the Combustion of Alum with Phlogistic Substances, and on the Changes effected on Air in which the Pyrophorus was burned.”

- “On the Vitriolisation of Martial Pyrites.”

- “General Considerations on the Nature of Acids, and on the Principles of which they are composed.”

- “On the Combination of the Matter of Fire with Evaporable Fluids; and on the Formation of Elastic Aëriform Fluids.”

- “Reflections on Phlogiston”, translation by Nicholas W. Best of “Réflexions sur le phlogistique, pour servir de suite à la théorie de la combustion et de la calcination” (read to the Académie Royale des Sciences over two nights, 28 June and 13 July 1783). Published in two parts:

- Best, Nicholas W. (2015). “Lavoisier’s “Reflections on phlogiston” I: Against phlogiston theory”. Foundations of Chemistry. 17 (2): 361–378. doi:10.1007/s10698-015-9220-5. S2CID 170422925.

- Best, Nicholas W. (2016). “Lavoisier’s “Reflections on phlogiston” II: On the nature of heat”. Foundations of Chemistry. 18 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1007/s10698-015-9236-x. S2CID 94677080.

- Method of chymical nomenclature: proposed by Messrs. De Moreau, Lavoisier, Bertholet, and De Fourcroy (1788) Dictionary

- Elements of Chemistry, in a New Systematic Order, Containing All the Modern Discoveries (Edinburgh: William Creech, 1790; New York: Dover, 1965) translation by Robert Kerr of Traité élémentaire de chimie. ISBN 978-0-486-64624-4 (Dover).

- 1799 edition

- 1802 edition: volume 1, volume 2

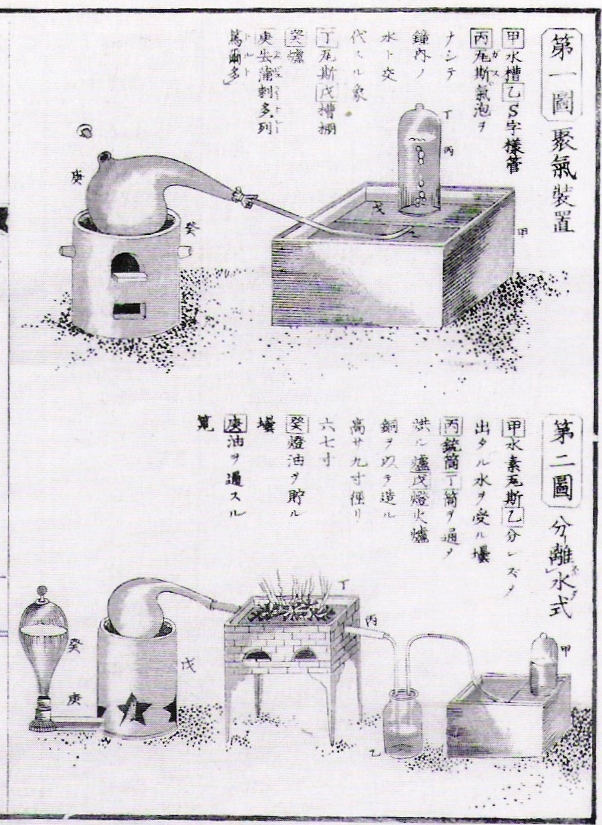

- Some illustrations from 1793 edition

- Some more illustrations from the Science History Institute

- More illustrations (from Collected Works) from the Science History Institute

AWARDS

"The art of concluding from experience and observation consists in evaluating probabilities, in estimating if they are high or numerous enough to constitute proof. This type of calculation is more complicated and more difficult than one might think. It demands a great sagacity generally above the power of common people. The success of charlatans, sorcerors, and alchemists—and all those who abuse public credulity—is founded on errors in this type of calculation."

Antoine Lavoisier and Benjamin Franklin, Rapport des commissaires chargés par le roi de l'examen du magnétisme animal (Imprimerie royale, 1784), trans. Stephen Jay Gould, "The Chain of Reason versus the Chain of Thumbs", Bully for Brontosaurus (W.W. Norton, 1991), p. 195

Antoine Lavoisier

|

Library resources about |

| By Antoine Lavoisier |

|---|

- Archives: Fonds Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier, Le Comité Lavoisier, Académie des sciences

- Panopticon Lavoisier a virtual museum of Antoine Lavoisier

- Bibliography at Panopticon Lavoisier

- Les Œuvres de Lavoisier

- About his work

- Location of Lavoisier’s laboratory in Paris

- Radio 4 program on the discovery of oxygen by the BBC

- Who was the first to classify materials as “compounds”? – Fred Senese

- Cornell University’s Lavoisier collection

- His writings

- Works by Antoine Lavoisier at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Antoine Lavoisier at Internet Archive

- Les Œuvres de Lavoisier (The Complete Works of Lavoisier) edited by Pietro Corsi (Oxford University) and Patrice Bret (CNRS) (in French)

- Oeuvres de Lavoisier (Works of Lavoisier) at Gallica BnF in six volumes. (in French)

- WorldCat author page

- Title page, woodcuts, and copperplate engravings by Madame Lavoisier from a 1789 first edition of Traité élémentaire de chimie (all images freely available for download in a variety of formats from Science History Institute Digital Collections at digital.sciencehistory.org.

GIOBERT

INTRODUCED LAVOISIER'S THEORIES TO ITALY

Giovanni Antonio Giobert also known as Jean-Antoine Giobert (1761- 1834) was an Italian chemist and mineralogist who studied magnetism, galvanism, and agricultural chemistry.

He introduced Antoine Lavoisier's theories to Italy, and built a phosphorus-based eudiometer sufficiently sensitive to measure atmospheric carbon dioxide and oxygen.

He published experimental work in the debate over whether water was a simple element or chemical composition of hydrogen and oxygen. In 1792, his work on the refutation of phlogiston theory won a prize competition on the subject, put forward by the Academy of Letters and Sciences of Mantua in 1790 and 1791. His "Examen chimique de la doctrine du phlogistique et de la doctrine des pneumatistes par rapport à la nature de l 'eau", presented to the Académie royale des Sciences of Turin on 18 March 1792, is considered the most original defense of Lavoisier's theory of water composition to appear in Italy.

Giobert contributed significantly to eudiometry, the study of gas composition, by further developing Lavoisier's eudiometer. Giobert built a phosphorus-based instrument sufficiently sensitive to measure atmospheric carbon dioxide and oxygen. He used it to compare the air quality of Turin with higher altitude Vinadio. A number of other researchers developed variants on his eudiometer, including Spallanzani, Humphry Davy, John Dalton, and Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac.

In 1790, the University of Turin established the Deputazione per la Tinture, an ambitious project whose goals included the study of dye plants, the review of dyeing processes, cataloguing of dyestuffs and establishing a library, improving artisan skills, working with foreign dyers and chemists, and using new chemicals and instruments to improve the state of the art in Piedmont. An imperial decree in 1810 encouraged the improvement of scientific and industrial techniques for using woad. Giobert was active as a chemical advisor and made important contributions to the dyeing industry, studying the chemistry of natural dyes including woad, indigo, and turkey red. For example, Giobert suggested that uneven bleaching of cotton with alkaline lye was a cause of variable color-fastness when the cloth was dyed. He helped to identify differences between animal- and plant-based dyes, and developed techniques for "animalizing" fibres with nitrogen gas to improve the solidity of the dye. Such techniques became widespread throughout the European dyeing industry. In 1811 Giobert worked with Raymond Latour on the development of blue dyes which became widely used. In 1813, Giobert was appointed director of the École impériale pour la fabrication de l'indigo in Turin, which was established to study industrial processing of indigo. Giobert identified a colorless form of indigo (sometimes called indigogen or 'white' indigo) in plants, convertible to indigo-blue through oxidation. For his work on the indigo color dyeing method, Giobert was made a knight (Cavaliere).

He identified the correct composition of the mineral Gioberite, a form of magnesite (MgCO3) found in the Piedmont area. Identifying its composition was an important contribution to the industry of pottery-making.

Giobert also developed the Gioberti tincture, which involved application of hydrochloric acid and potassium ferrocyanide. The Gioberti tincture was used in the 19th century and early 20th century to restore illegible writings or faded pictures, before less harsh chemical reagents were found. Gioberti tincture was used to show the original inscriptions of palimpsests by conservators at the Vatican.

Giobert was part of a Turin-based Comitato Galvanico that supported the theories of Luigi Galvani against those of Alessandro Volta. Giobert carried out research into the conduction of electricity and the forming of precipitates along a wire in a galvanic apparatus.

The period in which Giobert was active was one of considerable political upheaval. The University of Turin was closed in both 1797 and 1799 due to political events. Giobert was a francophile and a strong republican supporter of Napoleon. In 1798 he was appointed to the provisional government of Piedmont (Il Governo Provvisorio della Nazione Piemontese), only to be imprisoned in 1799 when the Austrians briefly took power. Following his release, he became a professor at the University of Turin. In 1814, after the restoration of King Victor Emmanuel I, Giobert was one of nine professors removed from their teaching positions in Turin due to their political involvement.

Giobert died on 14 September 1834 in Millefiori near Turin. He is remembered by the town of Asti, which named a street in his honor in 1868, and established the Istituto Giobert di Asti in 1882. He was also honored by the town of Mongardino which named the Scuola Elementare Giobert di Mongardino in his honor. Scholars continue to study his life and work. A bust of Giobert was unveiled at the “Giobert: da Mongardino alla nuova chimica” conference in Mongardino on October 20, 2013.

WORKS

- Dissertazione sopra il quesito: Verificare con più accertati mezzi chimici, se l’aqua sia un corpo composto di diversi arie … oppure sia un vero elemento simplice, etc. (Dissertation on the question: Verify with more established chemical means, if the water is a body composed of different components … or it is a real simple element, etc.). Mantova (Mantua). 1794.

- Raccolta di memorie spettanti all’ agricoltura [microform] : economia di casa, commercio, arti, e manifatture (Collection of Memories Affecting Agriculture [microform]: Home Economics, Commerce, Arts, and Manufacturing). Torino (Turin): Presso Costanzo, e Fenoglio. 1791.

- “Ueber einige galvanische Versuche von Giobert. Aus einem Briefe desselben an van Mons. (On some galvanic experiments by Giobert. From a letter to van Mons.)”. Neues Allgemeines Journal der Chemie. Frölich, Berlin. 3 (2): 219. 1804.

- Traité sur le pastel et l’extraction de son Indigo. Paris: Imprimerie impériale. 1813.

- Nachricht für die Einwohner des Ober-Ems-Departements über den Anbau und die Benutzung des Waid; ein Auszug aus dem in diesem Jahre in Paris erschienenen Werke: “Traité sur le Pastel et l’extraction de son Indigo” (News for the inhabitants of the Upper Ems Department on the cultivation and use of the woad; an extract from the work published this year in Paris: “Traité sur le Pastel et l’extraction de son Indigo”.). Osnabrück: R. Koch. 1813.

- Del sovescio di segale di G.A. Giobert lettere dilucidative e comenti. Turin: Gaetano Balbino. 1819.

- Des Eaux thermales et acidules de l’Échaillon en Maurienne. Essai. Turin: Pomba et Fils. 1822.

- De l’écorce du robinier (Robinia pseudo-accacia L.), et de ses usages dans les arts et l’économie domestique (From the bark of the Robinia pseudo-accacia L.; its uses in the arts and domestic economy). Mme Huzard (Huzard née Vallat la Chapelle). 1833.

| Library resources about Giovanni Antonio Giobert |

| By Giovanni Antonio Giobert |

|---|

referencs

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phlogiston_theory

- Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- Mauskop, Seymour (1 November 2002). “Richard Kirwan’s Phlogiston Theory: Its Success and Fate”. Ambix. 49 (3): 185–205. doi:10.1179/amb.2002.49.3.185. ISSN 0002-6980. PMID 12833914. S2CID 170853908.

- James Bryant Conant, ed. The Overthrow of Phlogiston Theory: The Chemical Revolution of 1775–1789. Cambridge: Harvard University Press (1950), 14. OCLC 301515203.

- “Priestley, Joseph”. Spaceship-earth.de. Archived from the original on 2 March 2009. Retrieved 5 June 2009.

- Ladenburg, Dr. A (1911). Lectures on the History of Chemistry. University of Chicago Press. p. 4. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- Bowler, Peter J (2005). Making modern science: A historical survey. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 60. ISBN 9780226068602.

- Becher, Physica Subterranea p. 256 et seq.

- Brock, William Hodson (1993). The Norton history of chemistry (1st American ed.). New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-03536-0.

- White, John Henry (1973). The History of Phlogiston Theory. New York: AMS Press Inc. ISBN 978-0404069308.

- Leicester, Henry M.; Klickstein, Herbert S. (1965). A Source Book in Chemistry. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Mason, Stephen F., (1962). A History of the Sciences (revised edition). New York: Collier Books. Ch. 26.

- Ladenburg 1911, pp. 6–7.

- “Chemistry”, Encyclopedia Britannica, 1911

- Abbri, Ferdinando (2001). “GIOBERT, Giovanni Antonio”. Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani [Biographical Dictionary of the Italians]. 55. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- Boyle, R. A (1673). Discovery of the Perviousness of Glass to Ponderable Parts of Flame. London: Essays of Effluvium. pp. 57–85.

- For a discussion of how the term phlogiston was understood during the eighteenth century, see: James R Partington & Douglas McKie; “Historical studies on the phlogiston theory”; Annals of Science, 1937, 2, 361–404; 1938, 3, 1–58; and 337–371; 1939, 5, 113–149. Reprinted 1981 as ISBN 978-0-405-13895-9.

- Priestley, Joseph (1796). Experiments and Observations Relating to the Analysis of Atmospherical Air: Also, Farther Experiments Relating to the Generation of Air from Water. … To which are Added, Considerations on the Doctrine of Phlogiston, and the Decomposition of Water. London: J. Johnson. p. 42.

- Joseph Priestley (1794). Heads of lectures on a course of experimental philosophy. London: Joseph Johnson.

- Best, Nicholas W. (1 July 2015). “Lavoisier’s “Reflections on phlogiston” I: against phlogiston theory”. Foundations of Chemistry. 17 (2): 137–151. doi:10.1007/s10698-015-9220-5. ISSN 1572-8463. S2CID 254510272.

- Ihde, Aaron (1964). The Development of Modern Chemistry. New York: Harper & Row. p. 81.

- Rayner-Canham, Marelene; Rayner-Canham, Geoffrey (2001). Women in chemistry: their changing roles from alchemical times to the mid-twentieth century. Philadelphia: Chemical Heritage Foundation. pp. 28–31. ISBN 978-0941901277. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- Datta, N. C. (2005). The story of chemistry. Hyderabad: Universities Press. pp. 247–250. ISBN 9788173715303. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- Partington, J. R.; McKie, Douglas (1981). Historical Studies on the Phlogiston Theory. Arno Press. ISBN 978-0405138508.

Quotes

- Quotations related to Phlogiston theory at Wikiquote

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phlogiston_theory

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J._J._Becher

- Bowler, Peter J (2005). Making modern science: A historical survey. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 60. ISBN 9780226068602.

- Becher, Physica Subterranea p. 256 et seq.

- Brock, William Hodson (1993). The Norton history of chemistry (1st American ed.). New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-03536-0.

- White, John Henry (1973). The History of Phlogiston Theory. New York: AMS Press Inc. ISBN 978-0404069308.

- Leicester, Henry M.; Klickstein, Herbert S. (1965). A Source Book in Chemistry. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Chisholm 1911, p. 602.

- Smith, Pamela H. (2016). The Business of Alchemy: Science and Culture in the Holy Roman Empire. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691173238, p. 40/41; see also: ‘The Emperor’s Mercantile Alchemist’ in: Greenberg, Arthur (2006) – From Alchemy to Chemistry in Picture and Story. Hoboken N.J. : John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978 0 470 08523 3. p. 231f. Chisholm writes in the 11th. ed. of the Encyclopædia Britannica that Becher “published an edition of Salzthal’s Tractatus de lapide trismegisto.”

- Chisholm 1911, pp. 602–603. …appointed physician to the elector of Bavaria; but in 1670 he was again in Vienna advising on the establishment of a silk factory and propounding schemes for a great company to trade with the Low Countries and for a canal to unite the Rhine and Danube.

- Mayr, Otto (1971). “Adam Smith and the Concept of the Feedback System: Economic Thought and Technology in 18th-Century Britain”. Technology and Culture. 12 (1): 1–22. doi:10.2307/3102276. ISSN 0040-165X. JSTOR 3102276.

- Chisholm 1911, p. 603.

- Charles W. Ingrao, The Habsburg Monarchy: 1618-1815, New York: Cambridge University Press, Second edition. ISBN 0-521-78505-7; p. 92-93. Becher was the most original and influential theorist of Austrian cameralism. He sought to balance between the need to reinstate postwar levels of population and production both in the countryside and the towns. By leaning more seriously on trade and commerce, Austrian cameralism helped to transfer attention to the troubles of the monarchy’s urban economies. Ferdinand II had already taken some corrective steps before he died by attempting to ease the debts of the Bohemian towns and to put limits on some of the land-holding nobility’s commercial rights. Even though preceding Habsburgs had held the guilds responsible for their restrictiveness, wastefulness, and the poor value of the merchandise they created, Ferdinand II ramped up the pressure by extending rights to private artisans who usually then earned the fortification of powerful local leaders such as seigneurs, military commanders, churches, and universities. An edict by Leopold I in 1689 had granted the government the right to monitor and control the number of masters and cut down on the monopoly effect of guild operations. Even previous to this, Becher, who was against all forms of monopoly, surmised that a third of the Austrian lands’ 150,000 artisans were “Schwarzarbeiter” who were not in a guild. “Immediately after the Thirty Years’ War the Bohemian towns had petitioned Ferdinand to refine its own raw materials into more finished goods for export. Becher became the leading force in attempting this conversion. By 1666 he had inspired the creation of a Commerce Commission (Kommerzkollegium) in Vienna, as well as the reestablishment of the first postwar silk plantation on the Lower Austrian estates of Hofkammer President Sinzendorf. Becher then subsequently helped create a Kunst- und Werkhaus in which foreign masters trained non-guild artisans in the production of finished goods. By 1672 he had promoted the construction of a wool factory in Linz. Four years later he established a textile workhouse for vagabonds in the Boemian town of Tabor that eventually employed 186 spinners under his own directorship.” Some of Becher’s projects met with limited success. In time Linz’s new wool factory even became one of the largest and most important in Europe. Yet most of the government initiatives ended in failure.

- Bill Bryson, A Short History of Nearly Everything, London: Black Swan, 2003 edition. ISBN 0-552-99704-8; p. 130.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johann_Joachim_Becherhttps

Sources

- Smith, Pamela H. (1994). The Business of Alchemy: Science and Culture in the Holy Roman Empire. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Ingrao, Charles W. (2005). The Habsburg Monarchy: 1618–1815. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Becher, Johann Joachim“. Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 602–603.

- Anthony Endres, Neoclassical Microeconomic Theory: the founding Austrian version (London: Routledge Press, 1997).

- Erik Grimmer-Solem, The Rise of Historical Economics and Social Reform in Germany 1864–1894 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003)

- Phlogiston Theory at Wikipedia

- Johann Joachim Becher at Wikipedia

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phlogiston_theory

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Georg_Ernst_Stahl

- Stahl’s date of birth is often given erroneously as 1660. The correct date is recorded in the parish register of St. John’s church, Ansbach. See Gottlieb, B.J. (1942). “Vitalistisches Denken in Deutschland im Anschluss an Georg Ernst Stahl”. Klinische Wochenschrift. 21 (20): 445–448. doi:10.1007/bf01773817. S2CID 41987182.

- Ku-ming Chang (2008)”Stahl, Georg Ernst”, Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Vol. 24, from Cengage Learning

- “Adreßbuch Deutscher Chemiker 1953/54. Gemeinsam herausgegeben von Gesellschaft Deutscher Chemiker und Verlag Chemie, Weinheim/Bergstraße. Verlag Chemie GmbH. (1953). 450 S.”. Starch – Stärke. 6 (12): 312. 1954. doi:10.1002/star.19540061211. ISSN 0038-9056.

- “Georg Ernst Stahl”. Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2013. Web. 25 May 2013

- Magill, Frank N. “Georg Ernst Stahl”, Dictionary of World Biography. 1st ed. 1999. Print.

- Francesco Paolo de Ceglia: Hoffmann and Stahl. Documents and Reflections on the Dispute. in History of Universities 22/1 (2007): 98–140.

- Smets, Alexis. The Controversy Between Leibniz and Stahl on the Theory of Chemistry Archived 2012-04-25 at the Wayback Machine, Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on History of Chemistry

- The Leibniz-Stahl Controversy (2016), transl. and edited by F. Duchesneau and J.H. Smith, Yale UP (536pp.)

- Vartanian, Aram (2006) “Stahl, Georg Ernst (1660–1734)”, Encyclopedia of Philosophy, editor Donald M. Borchert. 2nd ed. Vol. 9. Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA. 202–203. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 26 May 2013.

- Chang, K (2004). “Motus Tonicus: Georg Ernst Stahl’s Formulation of Tonic Motion and Early Modern Medical Thought”. Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 78 (4): 767–803. doi:10.1353/bhm.2004.0161. PMID 15591695. S2CID 12488842. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- Hudson, John (1992). The History of Chemistry. Hong Kong: The Macmillan Press. p. 47. ISBN 0-412-03641-X.

- Hopper, Christopher P.; Zambrana, Paige N.; Goebel, Ulrich; Wollborn, Jakob (June 2021). “A brief history of carbon monoxide and its therapeutic origins”. Nitric Oxide. 111–112: 45–63. doi:10.1016/j.niox.2021.04.001.

- Hélène Metzger (1926) “La philosophie de la matière chez Stahl et ses disciples” Isis >8: 427–464.

- Hélène Metzger (1930) Newton, Stahl, Boerhaave et la Doctrine Chemique

- Lawrence M. Principe (2007) Chymists and Chymistry

- White, John Henry (1973). The History of Phlogiston Theory. New York: AMS Press Inc. ISBN 978-0404069308.

- Leicester, Henry M.; Klickstein, Herbert S. (1965). A Source Book in Chemistry. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Mason, Stephen F., (1962). A History of the Sciences (revised edition). New York: Collier Books. Ch. 26.Ladenburg 1911, pp. 6–7.

- Phlogiston at Wikipedia

- Georg Ernst Stahl at Wikipedia

External links

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phlogiston_theory

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antoine-Laurent_de_Lavoisier

- “Lavoisier, Antoine Laurent”. Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021.

- “Lavoisier”. Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- “Lavoisier”. Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- (in French) Lavoisier, le parcours d’un scientifique révolutionnaire CNRS (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique)

- Schwinger, Julian (1986). Einstein’s Legacy. New York: Scientific American Library. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-7167-5011-6.

- In his table of the elements, Lavoisier listed five “salifiable earths” (i.e., ores that could be made to react with acids to produce salts (salis = salt, in Latin)): chaux (calcium oxide), magnésie (magnesia, magnesium oxide), baryte (barium sulfate), alumine (alumina, aluminium oxide), and silice (silica, silicon dioxide). About these “elements”, Lavoisier speculates: “We are probably only acquainted as yet with a part of the metallic substances existing in nature, as all those which have a stronger affinity to oxygen than carbon possesses, are incapable, hitherto, of being reduced to a metallic state, and consequently, being only presented to our observation under the form of oxyds, are confounded with earths. It is extremely probable that barytes, which we have just now arranged with earths, is in this situation; for in many experiments it exhibits properties nearly approaching to those of metallic bodies. It is even possible that all the substances we call earths may be only metallic oxyds, irreducible by any hitherto known process.” – from p. 218 of: Lavoisier with Robert Kerr, trans., Elements of Chemistry, …, 4th ed. (Edinburgh, Scotland: William Creech, 1799). (The original passage appears in: Lavoisier, Traité Élémentaire de Chimie, … (Paris, France: Cuchet, 1789), vol. 1, p. 174.)

- Schama, Simon (1989). Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. Alfred A Knopf. p. 73.

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). “Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier” . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Lavoisier, Antoine Laurent” . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 295.

- Yount, Lisa (2008). Antoine Lavoisier : founder of modern chemistry. Berkeley Heights, NJ: Enslow Publishers. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-7660-3011-4. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- Duveen, Dennis I. (1965). Supplement to a bibliography of the works of Antoine Laurent Lavoisier, 1743–1794. London: Dawsons.

- McKie, Douglas (1935). Bibliographic Details Antoine Lavoisier, the father of modern chemistry, by Douglas McKie … With an introduction by F.G. Donnan. London: V. Gollancz ltd.

- Bibliographic Details Lavoisier in perspective / edited by Marco Beretta. Munich: Deutsches Museum. 2005.

- Bell, Madison Smart (2005). Lavoisier in the year one. New York: W.W. Norton.

- McKie, Douglas (1952). Antoine Lavoisier: scientist, economist, social reformer. New York: Schuman.

- Citizens, Simon Schama. Penguin 1989 p. 236

- Eagle, Cassandra T.; Jennifer Sloan (1998). “Marie Anne Paulze Lavoisier: The Mother of Modern Chemistry”. The Chemical Educator. 3 (5): 1–18. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.472.7513. doi:10.1007/s00897980249a. S2CID 97557390.

- Donovan, Arthur (1996). Antoine Lavoisier: Science, Administration, and Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 273. ISBN 978-0-521-56672-8.

- Jean-Pierre Poirier (1998). Lavoisier: Chemist, Biologist, Economist. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 24–26. ISBN 978-0-8122-1649-3.

- W.R. Aykroyd (12 May 2014). Three Philosophers: Lavoisier, Priestley and Cavendish. Elsevier Science. pp. 168–170. ISBN 978-1-4831-9445-5.

- Arthur Donovan (11 April 1996). Antoine Lavoisier: Science, Administration and Revolution. Cambridge University Press. pp. 123–125. ISBN 978-0-521-56672-8.

- Citizens, Simon Schama, Penguin 1989 p. 313

- Dutton, William S. (1942), Du Pont: One Hundred and Forty Years, Charles Scribner’s Sons, LCCN 42011897.

- Chronicle of the French Revolution, Jacques Legrand, Longman 1989, p. 216 ISBN 0-582-05194-0

- Companion to the French Revolution, John Paxton, Facts on File Publications 1988, p. 120

- A Cultural History of the French Revolution, Emmet Kennedy, Yale University Press 1989, p. 193

- Chronicle of the French Revolution, Jacques Legrand, Longman 1989, p. 204 ISBN 0-582-05194-0

- Chronicle of the French Revolution, Jacques Legrand, Longman 1989, p. 356 ISBN 0-582-05194-0

- Chronicle of the French Revolution, Jacques Legrand, Longman 1989 ISBN 0-582-05194-0[page needed]

- O’Connor, J.J.; Robertson, E.F. (26 September 2006). “Joseph-Louis Lagrange”. Archived from the original on 2 May 2006. Retrieved 20 April 2006.

In September 1793 a law was passed ordering the arrest of all foreigners born in enemy countries and all their property to be confiscated. Lavoisier intervened on behalf of Lagrange, who certainly fell under the terms of the law. On 8 May 1794, after a trial that lasted less than a day, a revolutionary tribunal condemned Lavoisier and 27 others to death. Lagrange said on the death of Lavoisier, who was guillotined on the afternoon of the day of his trial

- Chronicle of the French Revolution, Longman 1989 p. 202 ISBN 0-582-05194-0

- “Today in History: 1794: Antoine Lavoisier, the father of modern chemistry, is executed on the guillotine during France’s Reign of Terror”. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013.

- Commenting on this quotation, Denis Duveen, an English expert on Lavoiser and a collector of his works, wrote that “it is pretty certain that it was never uttered”. For Duveen’s evidence, see the following: Duveen, Denis I. (February 1954). “Antoine Laurent Lavoisier and the French Revolution”. Journal of Chemical Education. 31 (2): 60–65. Bibcode:1954JChEd..31…60D. doi:10.1021/ed031p60

- Delambre, Jean-Baptiste (1867). Œuvres de Lagrange (in French). Gauthier-Villars. 15–57 – via Wikisource.

- Guerlac, Henry (1973). Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier – Chemist and Revolutionary. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. p. 130.

- (In French) M.-A. Paulze, épouse et collaboratrice de Lavoisier, Vesalius, VI, 2, 105–113, 2000, p. 110. (PDF)

- Guerlac, Henry (2019). “Lavoisier—the Crucial Year: The Background and Origin of His First Experiments on Combustion in 1772”. Cornell University Press. doi:10.7298/GX84-1A09.

- Lavoisier, Antoine (1777) “Mémoire sur la combustion en général” Archived 17 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine (“On Combustion in General”). Mémoires de l’Académie des sciences. English translation

- Petrucci R.H., Harwood W.S. and Herring F.G., General Chemistry (8th ed. Prentice-Hall 2002), p. 34

- “An Historical Note on the Conservation of Mass”.

- Duveen, Denis; Klickstein, Herbert (September 1954). “The Introduction of Lavoisier’s Chemical Nomenclature into America”. The History of Science Society. 45 (3).

- “Traité élémentaire de chimie : Présenté dans un ordre nouveau et d’après les découvertes modernes ; avec figures”. A Paris, Chez Cuchet, libraire, rue et Hôtel Serpente. 1789.

- Holleman, A. F.; Wiberg, Egon; Wiberg, Nils (2001). Inorganic Chemistry. Academic Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-12-352651-9.

- Golinski, Jan (1994). “Precision instruments and the demonstrative order of proof in Lavoisier’s chemistry” (PDF). Osiris. 9: 30–47. doi:10.1086/368728. JSTOR 301997. S2CID 95978870.

- Kirwan, Essay on Phlogiston, viii, xi.

- Lavoisier, Antoine (1778) “Considérations générales sur la nature des acides” Archived 17 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine (“General Considerations on the Nature of Acids”). Mémoires de l’Académie des sciences. lavoisier.cnrs.fr

- Gillispie, Charles Coulston (1960). The Edge of Objectivity: An Essay in the History of Scientific Ideas. Princeton University Press. p. 228. ISBN 0-691-02350-6.

- Lavoisier and Meusnier, “Développement” (cit. n. 27), pp. 205–209; cf. Holmes, Lavoisier (cn. 8), p. 237.

- See the “Advertisement,” p. vi of Kerr’s translation, and pp. xxvi–xxvii, xxviii of Douglas McKie’s introduction to the Dover edition.

- Is a Calorie a Calorie? American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Vol. 79, No. 5, 899S–906S, May 2004

- Levere, Trevor (2001). Transforming Matter. Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 72–73. ISBN 978-0-8018-6610-4.

- Gillespie, Charles C. (1996), Foreword to Lavoisier by Jean-Pierre Poirier, University of Pennsylvania Press, English Edition.

- Beretta, Marco (8 June 2022). The Arsenal of Eighteenth-Century Chemistry:The Laboratories of Antoine Laurent Lavoisier (1743-1794). Koninklijke Brill. p. 107. ISBN 9789004511217. Archived from the original on 24 December 2023. Retrieved 24 December 2023.

- “Place name detail: Mount Lavoisier”. New Zealand Gazetteer. New Zealand Geographic Board. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- “APS Member History”. search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- “Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier: The Chemical Revolution”. National Historic Chemical Landmarks. American Chemical Society. Archived from the original on 23 February 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- Guyton de Morveau, Louis Bernard; Lavoisier, Antoine Laurent; Berthollet, Claude-Louis; Fourcroy, Antoine-François de (1787). Méthode de Nomenclature Chimique. Paris, France: Chez Cuchet (Sous le Privilége de l’Académie des Sciences).

- “2015 Awardees”. American Chemical Society, Division of the History of Chemistry. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign School of Chemical Sciences. 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- “Citation for Chemical Breakthrough Award” (PDF). American Chemical Society, Division of the History of Chemistry. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign School of Chemical Sciences. 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- “Société Chimique de France”. www.societechimiquedefrance.fr. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- “International Society for Biological Calorimetry (ISBC) – About ISBC_”. biocalorimetry.ucoz.org. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- workflow-process-service. “The Lavoisier Medal honors exceptional scientists and engineers | DuPont USA”. www.dupont.com. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- “Le Prix Franklin–Lavoiser2018 a été décerné au Comité Lavoisier”. La Gazette du Laboratoire. 20 June 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- “Franklin-Lavoisier Prize”. Science History Institute. Archived from the original on 26 March 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- See Denis I. Duveen and Herbert S. Klickstein, “The “American” Edition of Lavoisier’s L’art de fabriquer le salin et la potasse,” The William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series 13:4 (October 1956), 493–498.

Further reading

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). “Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier” . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Bailly, J.-S., “Secret Report on Mesmerism or Animal Magnetism”, International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, Vol. 50, No. 4, (October 2002), pp. 364–368. doi:10.1080/00207140208410110

- Berthelot, M. (1890). La révolution chimique: Lavoisier. Paris: Alcan.

- Catalogue of Printed Works by and Memorabilia of Antoine Laurent Lavoisier, 1743–1794… Exhibited at the Grolier Club (New York, 1952).

- Daumas, M. (1955). Lavoisier, théoricien et expérimentateur. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

- Donovan, Arthur (1993). Antoine Lavoisier: Science, Administration, and Revolution. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Duveen, D.I. and H.S. Klickstein, A Bibliography of the Works of Antoine Laurent Lavoisier, 1743–1794 (London, 1954)

- Franklin, B., Majault, M.J., Le Roy, J.B., Sallin, C.L., Bailly, J.-S., d’Arcet, J., de Bory, G., Guillotin, J.-I. & Lavoisier, A., “Report of The Commissioners charged by the King with the Examination of Animal Magnetism”, International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, Vol.50, No.4, (October 2002), pp. 332–363. doi:10.1080/00207140208410109

- Grey, Vivian (1982). The Chemist Who Lost His Head: The Story of Antoine Lavoisier. Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, Inc. ISBN 9780698205598.

- Guerlac, Henry (1961). Lavoisier – The Crucial Year. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

- Holmes, Frederic Lawrence (1985). Lavoisier and the Chemistry of Life. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Holmes, Frederic Lawrence (1998). Antoine Lavoisier – The Next Crucial Year, or the Sources of his Quantitative Method in Chemistry. Princeton University Press.

- Jackson, Joe (2005). A World on Fire: A Heretic, An Aristocrat And The Race to Discover Oxygen. Viking.